I work on the software team at Voltus. We orchestrate distributed energy resources-large-scale electricity users, residential consumers, batteries, and generators-to make the electric grid more resilient and pay our customers well.

This is the story of migrating one hundred microservices from self-managed Kafka in Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2) to Amazon Managed Streaming for Apache Kafka (Amazon MSK).

Initial State

Kafka was introduced to the Voltus tech stack in 2019 and quickly became a critical piece of infrastructure. Today, many data flows that power the core of our product use Kafka, from continuous streaming of IOT time series data to domain event demand-response messages.

The initial state of Kafka at Voltus worked well enough for years. There were two self-managed Kafka clusters — one for development, one for production — deployed to Amazon EC2 via the server provisioning and configuration tool docker machine. They ran Kafka 1.0.0, two major versions behind the latest, in Docker containers from a Confluent Docker image. Zookeeper ran on dedicated Amazon EC2 instances.

The access patterns were documented. There was an internal web UI for tailing new records and performing basic administrative tasks. Downtime had been few and far between.

Why Migrate?

A number of deficiencies encouraged a migration away from our current Kafka setup.

Low Circus Factor

“Circus factor” is the number of people that would need to run away and join the circus for the remaining team to be left with insufficient process knowledge to function effectively. The engineer that was originally responsible for Kafka’s deployment and configuration was still at Voltus and available to help debug unexpected events. They represented a circus factor of one person— our team would have recovered much more slowly should anything have gone wrong with Kafka without them online to help debug.

Infrastructure Immutability

The once-standard docker machine commands necessary to deploy and configure Kafka were no longer documented, and the team had replaced the use of docker machine with Terraform and Nomad. Given that Kafka still used the old tooling, there was no easy path for applying upgrades, security patches, backups & recovery, configuring brokers and topics, scaling up instance size, broker count or storage. Nothing could be easily upgraded, scaled, or reconfigured without some risk of downtime.

Limited Authentication & Authorization

Authentication to access Kafka and authorization to access and control specific cluster resources were undifferentiated; if one could access Kafka, one could access and control everything with admin privileges.

Security groups controlled access to the Amazon EC2 instances outside our Nomad cluster, and engineers would need to manually update their current public IP address in these security groups through the Amazon EC2 console to access Kafka from their local machine.

In particular, this provided challenges for allowing third party services access to the Kafka cluster. We use ClickHouse as a core database at Voltus, which has a Kafka Engine table construct. This acts as a Kafka consumer to a topic, sinking data from the topic into a persistent table. Allowing the managed ClickHouse provider access to the entire cluster via IP whitelisting wasn’t secure or feasible, so the Kafka Engine tables weren’t available for use. In the meantime, we were maintaining our own tooling we had written to replicate some of the functionality of Kafka Engine tables.

Dated Metrics & Alerting

Originally, Kafka metrics were ingested via telegraf daemons and JMX. A Grafana dashboard existed for basic metrics like broker CPU, RAM, and disk utilization. A few years later, Voltus adopted Datadog as an observability platform. There was no clear path to ingest the JMX metrics into Datadog for dashboards and alerting. Instead of examining consumer group lag or record rates in dashboards while debugging, we inferred what metrics we could from service logs and behavior.

Security Concerns

In order to further harden our security, we needed to encrypt the disks on the Kafka cluster Amazon EC2 instances. We considered increasing all topic’s replication factors to 3 and manually restarting the cluster broker by broker as we encrypted the disk of each, but this process had the risk of downtime.

Difficulty Scaling Up

Voltus data volume and throughput requirements were increasing as we onboarded a variety of new distributed energy resources to the platform. Without a cluster configured for autoscaling, or at least a clear plan for manual actions taken to scale up the cluster, eventually some limits were going to be hit and an outage event would ensue.

Why a Managed Kafka Provider?

In our existing setup, Kafka was already running in the cloud. It would have been possible to improve the provisioning and configuration to achieve high availability, scalability, security and access, etc. without migrating to a managed provider.

The decision to use Amazon MSK was driven by a desire for Kafka to “just work” with as little maintenance as possible. One way to increase circus factor is to disseminate complex information through runbooks, documentation and other institutional knowledge. The more desirable option for our team was to decrease the net amount of complex information.

Abstracting away provisioning, maintenance, and configuration behind Amazon MSK’s API resulted in a higher Amazon Web Services (AWS) monthly service bill, but reduced total engineering time spent on maintenance, decreased risk of serious downtime, and increased feature velocity across the team. These benefits outweigh the increased cloud provider costs.

Which Managed Kafka Provider?

There are a few different managed Kafka providers out there. Some provide a wider feature set at a higher price tag.

Our team has the technical expertise to provision Amazon MSK clusters in a configuration that requires minimal ongoing maintenance. The tradeoff between plug-and-playability versus cost made Amazon MSK make the most sense for our situation.

Migration Preparation

We took a few steps to prepare for the migration. Use cases for Kafka were enumerated. Kafka clients in use were audited for their configuration capabilities. Requirements were written in the form of design documents and socialized for review across the team.

One quality-of-life improvement made to the existing Kafka cluster pre-migration was the introduction of Kowl, a fully featured Kafka Web UI. This allowed our team greater visibility into records across topics and partitions. Kowl also made administrative tasks like deleting test topics accessible at a click rather than a verbose shell command. The Kowl team was responsive and accommodating, and the product was solid compared to other Kafka Web UIs.

Note: Kowl has since been acquired and we have migrated to kafka-ui.

MSK Architecture and Configuration

We defined our Amazon MSK clusters using the AWS Terraform Provider, which does a good job staying up to date with the latest features.

Encryption, Authentication and Authorization

We first had to secure the cluster. Amazon MSK encrypts the data at rest by default, so disk encryption requirements were covered.

Amazon MSK offered multiple types of authentication:

- IAM Access Control: the AWS-native solution for both authentication and authorization

- Mutual TLS Authentication: client and server authenticate one another using TLS certificates managed in a private certificate authority

- SASL/SCRAM Authentication: username/password authentication with AWS Secrets Manager

It made sense for us to go with Mutual TLS. We were already using this mechanism elsewhere in our stack, the CAs and certificates could be managed through Terraform, and it ensured data in transit was encrypted.

Authorization was handled through native Kafka ACLs, which can also be managed through Terraform using an open source Kafka Terraform Provider.

Cluster Sizing

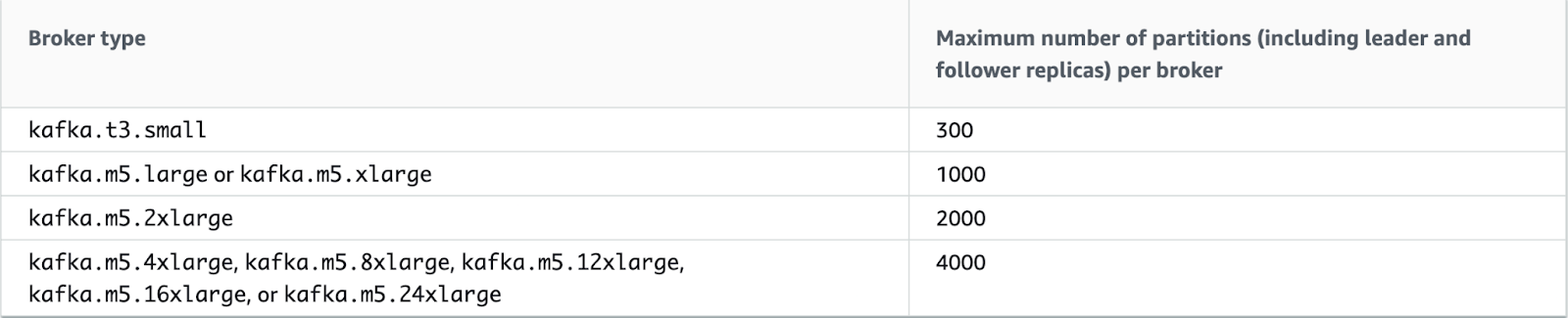

Cluster sizing decision were the most cost-sensitive. On the broker side, count, instance size, and storage were the main considerations.

Three brokers suited our volume and throughput requirements.

The number of partitions on the cluster determines the instance size. We accounted for the current number of partitions and allowed some room for growth. Amazon MSK can scale up instance size without downtime at a later date as long as the cluster is configured for availability on restart.

Storage per broker was primarily driven by the size and volume of records, topic-partition replication factor, per-topic partition count, and per-topic retention period.

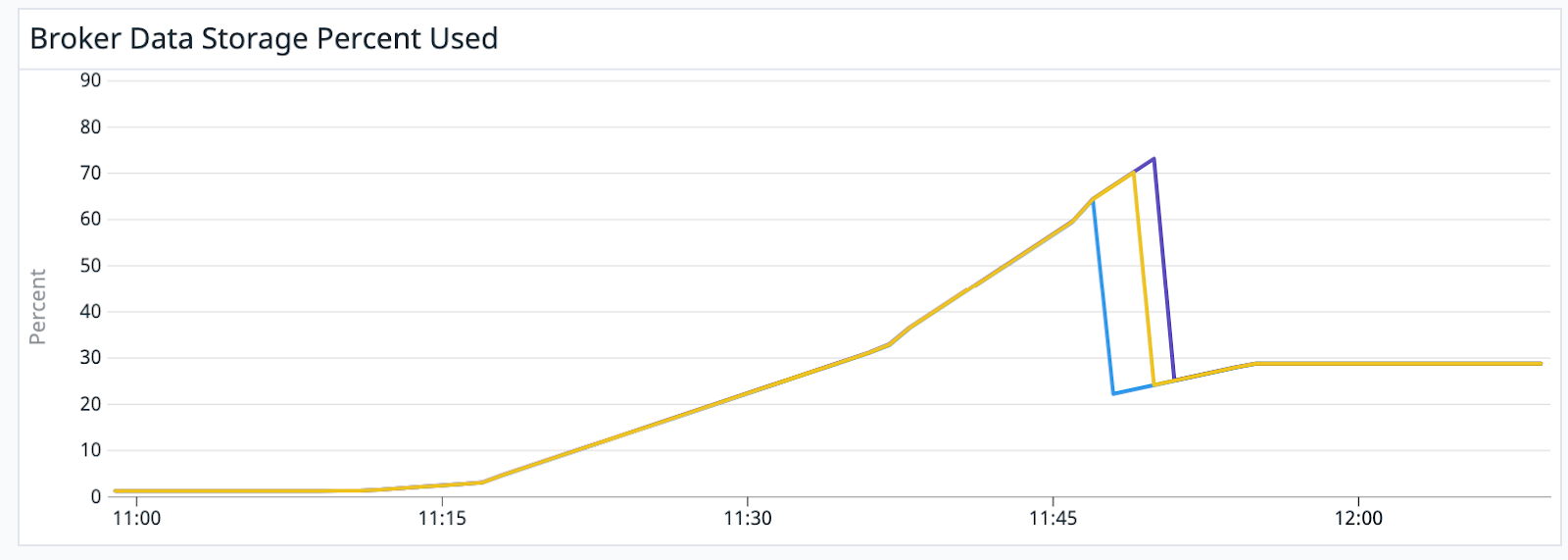

Implementing a reasonable auto-scaling policy for broker storage was straightforward, and a test of this policy showed brokers upscaling storage without downtime:

Network Access

Our fully distributed team needed to securely access Kafka from any network. No more manually adding public IPs to AWS security group whitelists. We already used Tailscale as our VPN at Voltus. The infrastructure team set up a Kafka proxy, configured to be accessible only over the Tailscale network, that not only proxied Kafka traffic but also abstracted away TLS authentication such that engineers didn’t need to manage their own certificates.

For services running in the Nomad cluster, similar Kafka proxies were run as system jobs–one per node.

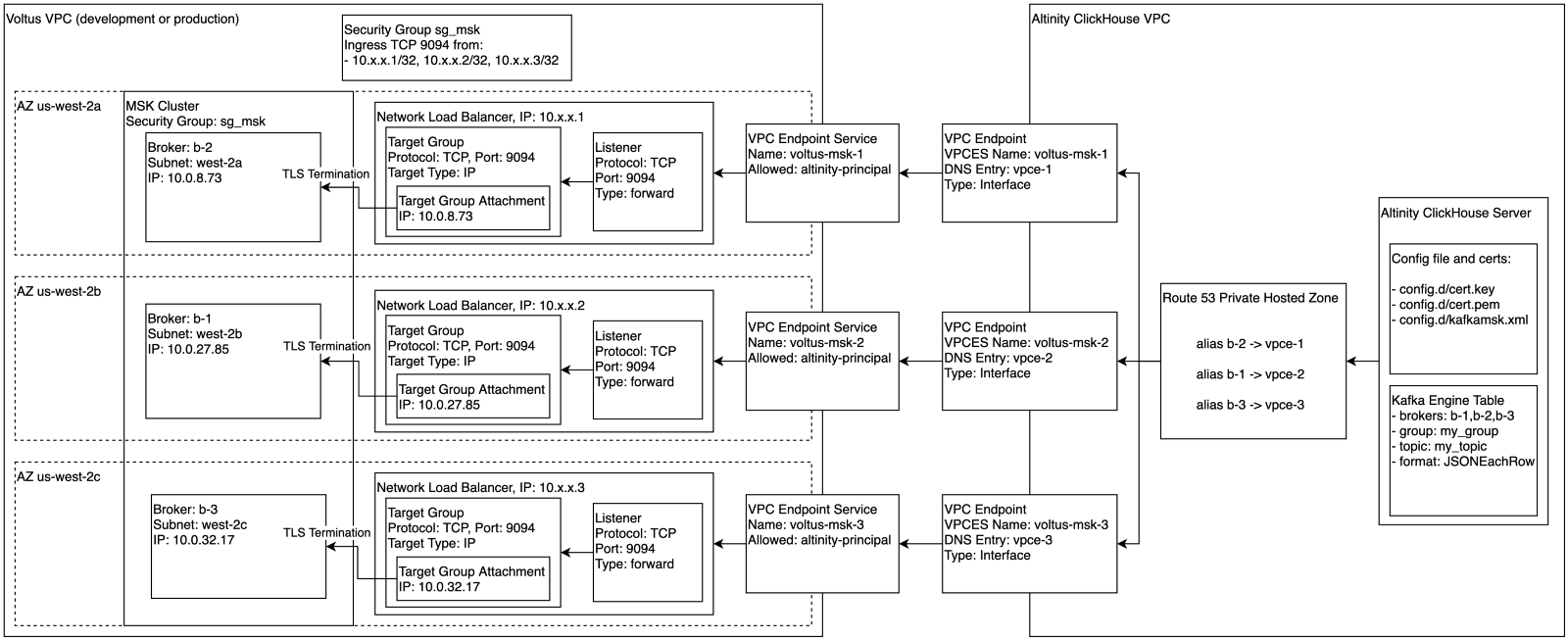

For external infrastructure like managed ClickHouse clusters, we set up security group rules, network load balancers, and VPC endpoint services. Our managed ClickHouse provider set up VPC Endpoints and Route 53 aliases in a private hosted zone. Voltus added certificate, key and passphrase to the ClickHouse cluster configuration, and persistent tables with Kafka Engine-backed sources became securely available.

Topic Management

In the prior setup, Kafka was configured to auto-create a topic if any consumer or producer attempted to access the topic without it already existing. This was convenient for developers, but put the cluster at risk of creating an unbounded number of topics if a script or application that programmatically generated topic names went awry.

We turned off auto-creation of topics in Amazon MSK, and now manage all topic creation, deletion, and (re)configuration through a Terraform provider. This means that topics are version controlled alongside application code, and Kafka cluster topic state is synced with code through a single Terraform command.

Observability through Datadog

As mentioned previously, Datadog is our single-pane-of-glass platform for application and infrastructure observability, including logs, alerts, and dashboards. The ingestion of Amazon MSK Cluster metrics into Datadog was straightforward through minimal additions to the Datadog agent configuration.

Having these metrics in Datadog has proved invaluable. Some key time series metrics Voltus now monitors include:

- Max consumer group offset by topic and consumer group

- Record count by broker and topic

- Standard metrics like CPU, data storage, partition count, network packets, and connection count by broker

They assisted in catching previously unobserved events, such as:

- Database ingestion service lagging by >50k records

- Kafka client connection failed to initialize on service redeployment

- Misconfigured Kafka clients not committing consumer group offsets, causing re-ingestion of duplicate records on service restart

Preparing for the Migration

Once the development and production environment Amazon MSK clusters were defined and provisioned through Terraform, the proxy services and inter-VPC connection pathways were running, and Datadog observability was setup, it was time to actually point everything from our self-managed Amazon EC2 Kafka clusters to the new Amazon MSK clusters.

MirrorMaker 2.0

Kafka ships with a tool called MirrorMaker 2.0, available since Kafka 2.4.0. MirrorMaker 2.0 is used to replicate state (data, topics, partitions, offsets, configuration etc.) across Kafka clusters. It is primarily used in migrations and cross-region cluster replication.

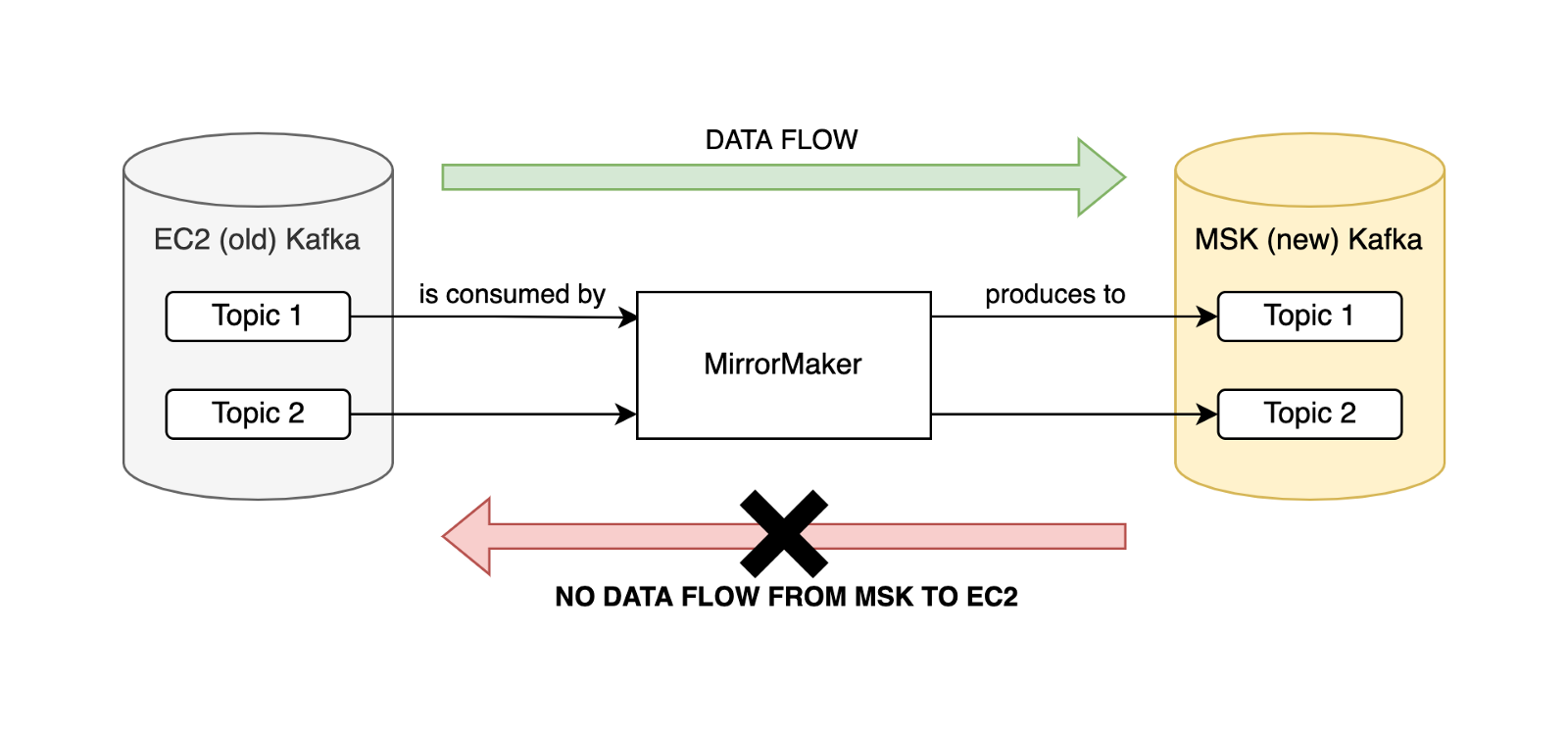

We deployed MirrorMaker 2.0 on Nomad, running between Amazon EC2 and Amazon MSK Kafka clusters in order to facilitate the zero-downtime migration. If both Kafka clusters contain the same data at a given time, it doesn’t matter which cluster a consumer is pointed at.

MirrorMaker was configured in an active/passive configuration, meaning data flow was unidirectional from old to new Kafka clusters.

An active/active configuration relies on prefixing the mirrored topics with the other cluster’s name and changing consumer configuration to consume from .*TOPIC_NAME rather than TOPIC_NAME, as explained in detail in this excellent blogpost.

The benefit of active/active is that it also doesn’t matter which cluster a producer is pointing to, as data ends up in all clusters either way.

We determined that the difficulty of ordering producer service migrations in an active/passive configuration was lower than that of reconfiguring all consumers to add the .* prefix required in the active/active configuration.

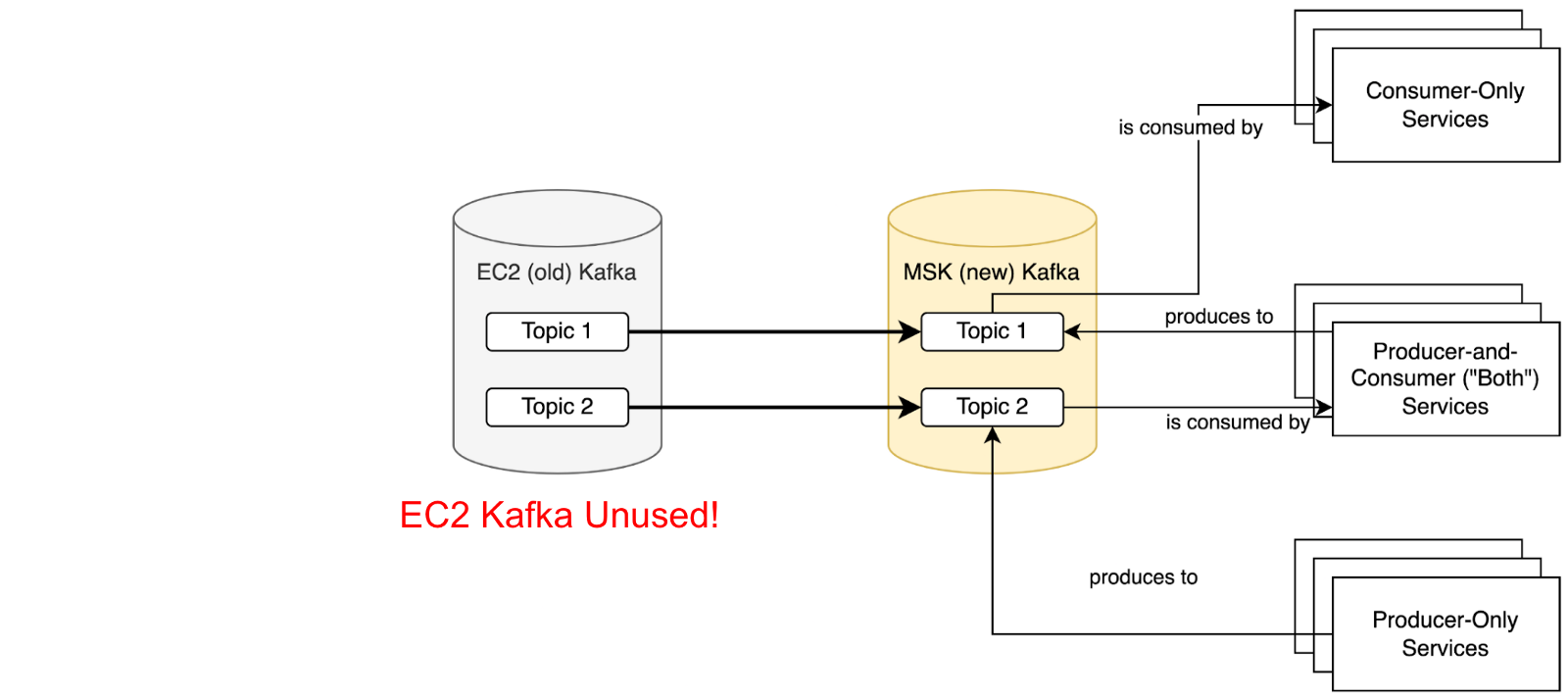

Service-Level Ordering for the Migration

The following process was planned to ensure no records were missed for any service during the migration.

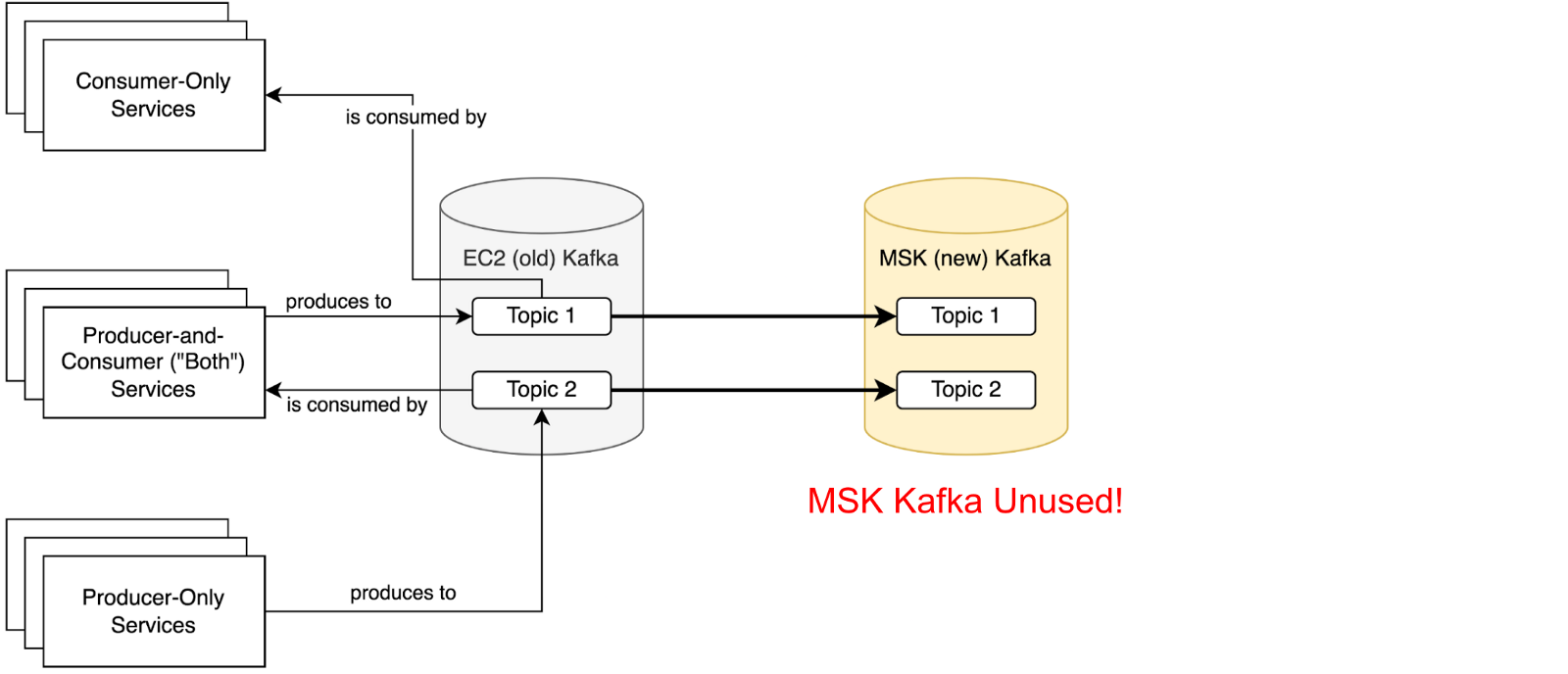

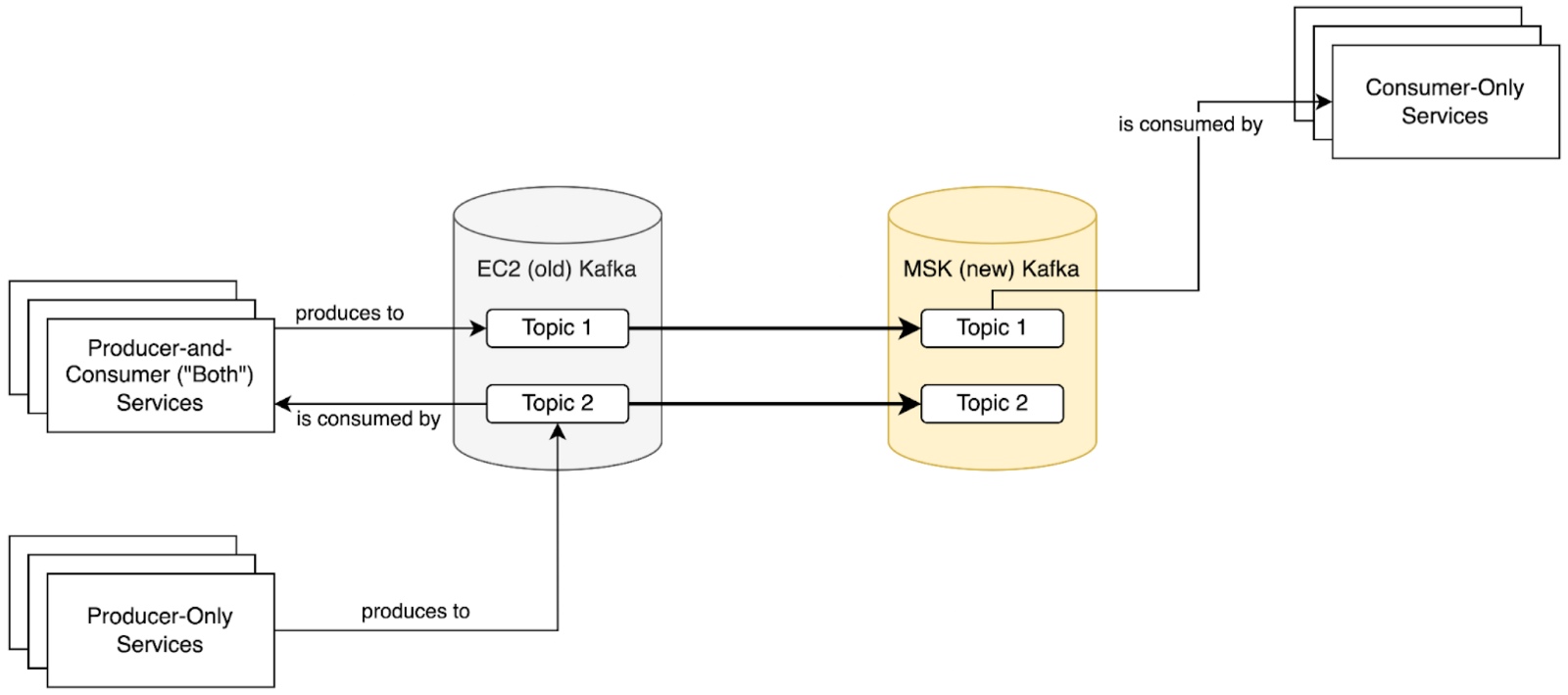

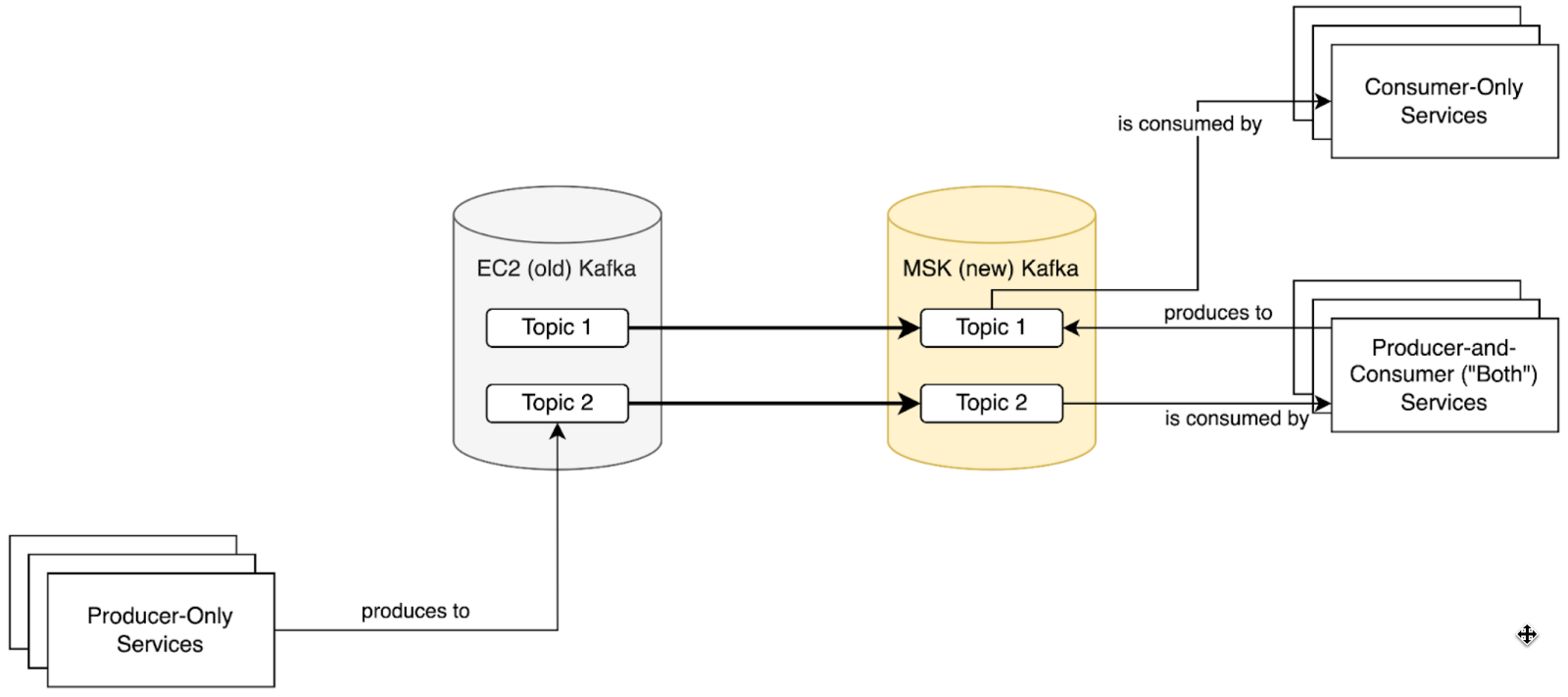

- Initial state, nothing consumes from or produces to MSK

- Point all services that only consume from Kafka topics at Amazon MSK, where records are replicated by MirrorMaker. Service migration order doesn’t matter at this stage.

- Point all services that both consume and produce from Kafka at Amazon MSK. Some migration ordering within this group is necessary based on the Kafka topic and service dependency graphs.

- Point all services that only produce records to Kafka at MSK. Service migration order once again doesn’t matter at this stage.

Once this final state is achieved, MirrorMaker 2.0 and Amazon EC2 self-managed Kafka clusters can be stopped and decommissioned.

The Migration

With MirrorMaker running and a spreadsheet to track service-level migration status setup, we were ready to undergo the actual migration.

We made runbooks for potential failure scenarios — what to do if MirrorMaker fails? Proxies fail? The Kafka cluster itself fails?

During one week that we called “Kafka Migration Week”, around 15 engineers actively participated in the migration of all one hundred services, changing connection strings from Amazon EC2 to Amazon MSK Kafka clusters in the codebase and redeploying the services they owned in the specified order.

None of the catastrophe-level runbooks needed referencing. The biggest snag during the week was realizing that MirrorMaker 2.0 only correctly mirrors consumer group offsets when both Kafka clusters are version 2.4.0 or above. Since the initial cluster was Kafka version 1.0.0, consumer group offsets were dropped despite MirrorMaker being configured to replicate them.

We determined that re-consuming records was preferable to missing records, so relevant consumers were reconfigured with auto.offset.reset as “earliest” for the migration, then reset to their prior values afterwards.

Conclusion

We have now been running Kafka on Amazon MSK for ~6 months now with zero downtime. The modernization of everything from access patterns, security, topic management, and observability has been a large boon to our Engineering organization. I hope this blogpost helped you on your journey to learn more about Kafka, complex migration paths, or any other adjacent infrastructure mentioned above.